Chapter 3: Digging to the Roots of JS

En esta Página

If you’ve read Chapters 1 and 2, and taken the time to digest and percolate, you’re hopefully starting to get JS a little more. If you skipped/skimmed them (especially Chapter 2), I recommend going back to spend some more time with that material.

In Chapter 2, we surveyed syntax, patterns, and behaviors at a high level. In this chapter, our attention shifts to some of the lower-level root characteristics of JS that underpin virtually every line of code we write.

Be aware: this chapter digs much deeper than you’re likely used to thinking about a programming language. My goal is to help you appreciate the core of how JS works, what makes it tick. This chapter should begin to answer some of the “Why?” questions that may be cropping up as you explore JS. However, this material is still not an exhaustive exposition of the language; that’s what the rest of the book series is for! Our goal here is still just to get started, and become more comfortable with, the feel of JS, how it ebbs and flows.

Don’t run so quickly through this material that you get lost in the weeds. As I’ve said a dozen times already, take your time. Even still, you’ll probably finish this chapter with remaining questions. That’s OK, because there’s a whole book series ahead of you to keep exploring!

Iteration

Since programs are essentially built to process data (and make decisions on that data), the patterns used to step through the data have a big impact on the program’s readability.

The iterator pattern has been around for decades, and suggests a “standardized” approach to consuming data from a source one chunk at a time. The idea is that it’s more common and helpful to iterate the data source—to progressively handle the collection of data by processing the first part, then the next, and so on, rather than handling the entire set all at once.

Imagine a data structure that represents a relational database SELECT query, which typically organizes the results as rows. If this query had only one or a couple of rows, you could handle the entire result set at once, and assign each row to a local variable, and perform whatever operations on that data that were appropriate.

But if the query has 100 or 1,000 (or more!) rows, you’ll need iterative processing to deal with this data (typically, a loop).

The iterator pattern defines a data structure called an “iterator” that has a reference to an underlying data source (like the query result rows), which exposes a method like next(). Calling next() returns the next piece of data (i.e., a “record” or “row” from a database query).

You don’t always know how many pieces of data that you will need to iterate through, so the pattern typically indicates completion by some special value or exception once you iterate through the entire set and go past the end.

The importance of the iterator pattern is in adhering to a standard way of processing data iteratively, which creates cleaner and easier to understand code, as opposed to having every data structure/source define its own custom way of handling its data.

After many years of various JS community efforts around mutually agreed-upon iteration techniques, ES6 standardized a specific protocol for the iterator pattern directly in the language. The protocol defines a next() method whose return is an object called an iterator result; the object has value and done properties, where done is a boolean that is false until the iteration over the underlying data source is complete.

Consuming Iterators

With the ES6 iteration protocol in place, it’s workable to consume a data source one value at a time, checking after each next() call for done to be true to stop the iteration. But this approach is rather manual, so ES6 also included several mechanisms (syntax and APIs) for standardized consumption of these iterators.

One such mechanism is the for..of loop:

// given an iterator of some data source:

var it = /* .. */;

// loop over its results one at a time

for (let val of it) {

console.log(`Iterator value: ${ val }`);

}

// Iterator value: ..

// Iterator value: ..

// ..| NOTE: |

|---|

We’ll omit the manual loop equivalent here, but it’s definitely less readable than the for..of loop! |

Another mechanism that’s often used for consuming iterators is the ... operator. This operator actually has two symmetrical forms: spread and rest (or gather, as I prefer). The spread form is an iterator-consumer.

To spread an iterator, you have to have something to spread it into. There are two possibilities in JS: an array or an argument list for a function call.

An array spread:

// spread an iterator into an array,

// with each iterated value occupying

// an array element position.

var vals = [ ...it ];A function call spread:

// spread an iterator into a function,

// call with each iterated value

// occupying an argument position.

doSomethingUseful( ...it );In both cases, the iterator-spread form of ... follows the iterator-consumption protocol (the same as the for..of loop) to retrieve all available values from an iterator and place (aka, spread) them into the receiving context (array, argument list).

Iterables

The iterator-consumption protocol is technically defined for consuming iterables; an iterable is a value that can be iterated over.

The protocol automatically creates an iterator instance from an iterable, and consumes just that iterator instance to its completion. This means a single iterable could be consumed more than once; each time, a new iterator instance would be created and used.

So where do we find iterables?

ES6 defined the basic data structure/collection types in JS as iterables. This includes strings, arrays, maps, sets, and others.

Consider:

// an array is an iterable

var arr = [ 10, 20, 30 ];

for (let val of arr) {

console.log(`Array value: ${ val }`);

}

// Array value: 10

// Array value: 20

// Array value: 30Since arrays are iterables, we can shallow-copy an array using iterator consumption via the ... spread operator:

var arrCopy = [ ...arr ];We can also iterate the characters in a string one at a time:

var greeting = "Hello world!";

var chars = [ ...greeting ];

chars;

// [ "H", "e", "l", "l", "o", " ",

// "w", "o", "r", "l", "d", "!" ]A Map data structure uses objects as keys, associating a value (of any type) with that object. Maps have a different default iteration than seen here, in that the iteration is not just over the map’s values but instead its entries. An entry is a tuple (2-element array) including both a key and a value.

Consider:

// given two DOM elements, `btn1` and `btn2`

var buttonNames = new Map();

buttonNames.set(btn1,"Button 1");

buttonNames.set(btn2,"Button 2");

for (let [btn,btnName] of buttonNames) {

btn.addEventListener("click",function onClick(){

console.log(`Clicked ${ btnName }`);

});

}In the for..of loop over the default map iteration, we use the [btn,btnName] syntax (called “array destructuring”) to break down each consumed tuple into the respective key/value pairs (btn1 / "Button 1" and btn2 / "Button 2").

Each of the built-in iterables in JS expose a default iteration, one which likely matches your intuition. But you can also choose a more specific iteration if necessary. For example, if we want to consume only the values of the above buttonNames map, we can call values() to get a values-only iterator:

for (let btnName of buttonNames.values()) {

console.log(btnName);

}

// Button 1

// Button 2Or if we want the index and value in an array iteration, we can make an entries iterator with the entries() method:

var arr = [ 10, 20, 30 ];

for (let [idx,val] of arr.entries()) {

console.log(`[${ idx }]: ${ val }`);

}

// [0]: 10

// [1]: 20

// [2]: 30For the most part, all built-in iterables in JS have three iterator forms available: keys-only (keys()), values-only (values()), and entries (entries()).

Beyond just using built-in iterables, you can also ensure your own data structures adhere to the iteration protocol; doing so means you opt into the ability to consume your data with for..of loops and the ... operator. “Standardizing” on this protocol means code that is overall more readily recognizable and readable.

| NOTE: |

|---|

| You may have noticed a nuanced shift that occurred in this discussion. We started by talking about consuming iterators, but then switched to talking about iterating over iterables. The iteration-consumption protocol expects an iterable, but the reason we can provide a direct iterator is that an iterator is just an iterable of itself! When creating an iterator instance from an existing iterator, the iterator itself is returned. |

Closure

Perhaps without realizing it, almost every JS developer has made use of closure. In fact, closure is one of the most pervasive programming functionalities across a majority of languages. It might even be as important to understand as variables or loops; that’s how fundamental it is.

Yet it feels kind of hidden, almost magical. And it’s often talked about in either very abstract or very informal terms, which does little to help us nail down exactly what it is.

We need to be able to recognize where closure is used in programs, as the presence or lack of closure is sometimes the cause of bugs (or even the cause of performance issues).

So let’s define closure in a pragmatic and concrete way:

Closure is when a function remembers and continues to access variables from outside its scope, even when the function is executed in a different scope.

We see two definitional characteristics here. First, closure is part of the nature of a function. Objects don’t get closures, functions do. Second, to observe a closure, you must execute a function in a different scope than where that function was originally defined.

Consider:

function greeting(msg) {

return function who(name) {

console.log(`${ msg }, ${ name }!`);

};

}

var hello = greeting("Hello");

var howdy = greeting("Howdy");

hello("Kyle");

// Hello, Kyle!

hello("Sarah");

// Hello, Sarah!

howdy("Grant");

// Howdy, Grant!First, the greeting(..) outer function is executed, creating an instance of the inner function who(..); that function closes over the variable msg, which is the parameter from the outer scope of greeting(..). When that inner function is returned, its reference is assigned to the hello variable in the outer scope. Then we call greeting(..) a second time, creating a new inner function instance, with a new closure over a new msg, and return that reference to be assigned to howdy.

When the greeting(..) function finishes running, normally we would expect all of its variables to be garbage collected (removed from memory). We’d expect each msg to go away, but they don’t. The reason is closure. Since the inner function instances are still alive (assigned to hello and howdy, respectively), their closures are still preserving the msg variables.

These closures are not a snapshot of the msg variable’s value; they are a direct link and preservation of the variable itself. That means closure can actually observe (or make!) updates to these variables over time.

function counter(step = 1) {

var count = 0;

return function increaseCount(){

count = count + step;

return count;

};

}

var incBy1 = counter(1);

var incBy3 = counter(3);

incBy1(); // 1

incBy1(); // 2

incBy3(); // 3

incBy3(); // 6

incBy3(); // 9Each instance of the inner increaseCount() function is closed over both the count and step variables from its outer counter(..) function’s scope. step remains the same over time, but count is updated on each invocation of that inner function. Since closure is over the variables and not just snapshots of the values, these updates are preserved.

Closure is most common when working with asynchronous code, such as with callbacks. Consider:

function getSomeData(url) {

ajax(url,function onResponse(resp){

console.log(

`Response (from ${ url }): ${ resp }`

);

});

}

getSomeData("https://some.url/wherever");

// Response (from https://some.url/wherever): ...The inner function onResponse(..) is closed over url, and thus preserves and remembers it until the Ajax call returns and executes onResponse(..). Even though getSomeData(..) finishes right away, the url parameter variable is kept alive in the closure for as long as needed.

It’s not necessary that the outer scope be a function—it usually is, but not always—just that there be at least one variable in an outer scope accessed from an inner function:

for (let [idx,btn] of buttons.entries()) {

btn.addEventListener("click",function onClick(){

console.log(`Clicked on button (${ idx })!`);

});

}Because this loop is using let declarations, each iteration gets new block-scoped (aka, local) idx and btn variables; the loop also creates a new inner onClick(..) function each time. That inner function closes over idx, preserving it for as long as the click handler is set on the btn. So when each button is clicked, its handler can print its associated index value, because the handler remembers its respective idx variable.

Remember: this closure is not over the value (like 1 or 3), but over the variable idx itself.

Closure is one of the most prevalent and important programming patterns in any language. But that’s especially true of JS; it’s hard to imagine doing anything useful without leveraging closure in one way or another.

If you’re still feeling unclear or shaky about closure, the majority of Book 2, Scope & Closures is focused on the topic.

this Keyword

One of JS’s most powerful mechanisms is also one of its most misunderstood: the this keyword. One common misconception is that a function’s this refers to the function itself. Because of how this works in other languages, another misconception is that this points the instance that a method belongs to. Both are incorrect.

As discussed previously, when a function is defined, it is attached to its enclosing scope via closure. Scope is the set of rules that controls how references to variables are resolved.

But functions also have another characteristic besides their scope that influences what they can access. This characteristic is best described as an execution context, and it’s exposed to the function via its this keyword.

Scope is static and contains a fixed set of variables available at the moment and location you define a function, but a function’s execution context is dynamic, entirely dependent on how it is called (regardless of where it is defined or even called from).

this is not a fixed characteristic of a function based on the function’s definition, but rather a dynamic characteristic that’s determined each time the function is called.

One way to think about the execution context is that it’s a tangible object whose properties are made available to a function while it executes. Compare that to scope, which can also be thought of as an object; except, the scope object is hidden inside the JS engine, it’s always the same for that function, and its properties take the form of identifier variables available inside the function.

function classroom(teacher) {

return function study() {

console.log(

`${ teacher } says to study ${ this.topic }`

);

};

}

var assignment = classroom("Kyle");The outer classroom(..) function makes no reference to a this keyword, so it’s just like any other function we’ve seen so far. But the inner study() function does reference this, which makes it a this-aware function. In other words, it’s a function that is dependent on its execution context.

| NOTE: |

|---|

study() is also closed over the teacher variable from its outer scope. |

The inner study() function returned by classroom("Kyle") is assigned to a variable called assignment. So how can assignment() (aka study()) be called?

assignment();

// Kyle says to study undefined -- Oops :(In this snippet, we call assignment() as a plain, normal function, without providing it any execution context.

Since this program is not in strict mode (see Chapter 1, “Strictly Speaking”), context-aware functions that are called without any context specified default the context to the global object (window in the browser). As there is no global variable named topic (and thus no such property on the global object), this.topic resolves to undefined.

Now consider:

var homework = {

topic: "JS",

assignment: assignment

};

homework.assignment();

// Kyle says to study JSA copy of the assignment function reference is set as a property on the homework object, and then it’s called as homework.assignment(). That means the this for that function call will be the homework object. Hence, this.topic resolves to "JS".

Lastly:

var otherHomework = {

topic: "Math"

};

assignment.call(otherHomework);

// Kyle says to study MathA third way to invoke a function is with the call(..) method, which takes an object (otherHomework here) to use for setting the this reference for the function call. The property reference this.topic resolves to "Math".

The same context-aware function invoked three different ways, gives different answers each time for what object this will reference.

The benefit of this-aware functions—and their dynamic context—is the ability to more flexibly re-use a single function with data from different objects. A function that closes over a scope can never reference a different scope or set of variables. But a function that has dynamic this context awareness can be quite helpful for certain tasks.

Prototypes

Where this is a characteristic of function execution, a prototype is a characteristic of an object, and specifically resolution of a property access.

Think about a prototype as a linkage between two objects; the linkage is hidden behind the scenes, though there are ways to expose and observe it. This prototype linkage occurs when an object is created; it’s linked to another object that already exists.

A series of objects linked together via prototypes is called the “prototype chain.”

The purpose of this prototype linkage (i.e., from an object B to another object A) is so that accesses against B for properties/methods that B does not have, are delegated to A to handle. Delegation of property/method access allows two (or more!) objects to cooperate with each other to perform a task.

Consider defining an object as a normal literal:

var homework = {

topic: "JS"

};The homework object only has a single property on it: topic. However, its default prototype linkage connects to the Object.prototype object, which has common built-in methods on it like toString() and valueOf(), among others.

We can observe this prototype linkage delegation from homework to Object.prototype:

homework.toString(); // [object Object]homework.toString() works even though homework doesn’t have a toString() method defined; the delegation invokes Object.prototype.toString() instead.

Object Linkage

To define an object prototype linkage, you can create the object using the Object.create(..) utility:

var homework = {

topic: "JS"

};

var otherHomework = Object.create(homework);

otherHomework.topic; // "JS"The first argument to Object.create(..) specifies an object to link the newly created object to, and then returns the newly created (and linked!) object.

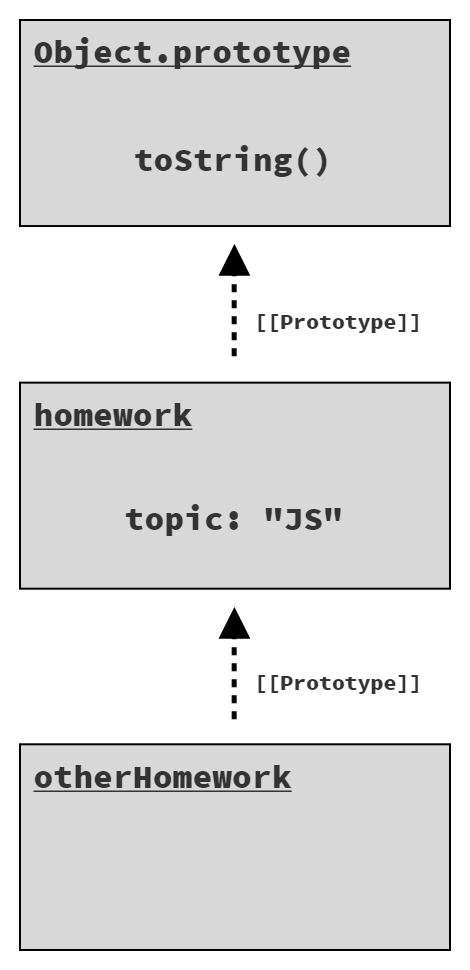

Figure 4 shows how the three objects (otherHomework, homework, and Object.prototype) are linked in a prototype chain:

Delegation through the prototype chain only applies for accesses to lookup the value in a property. If you assign to a property of an object, that will apply directly to the object regardless of where that object is prototype linked to.

| TIP: |

|---|

Object.create(null) creates an object that is not prototype linked anywhere, so it’s purely just a standalone object; in some circumstances, that may be preferable. |

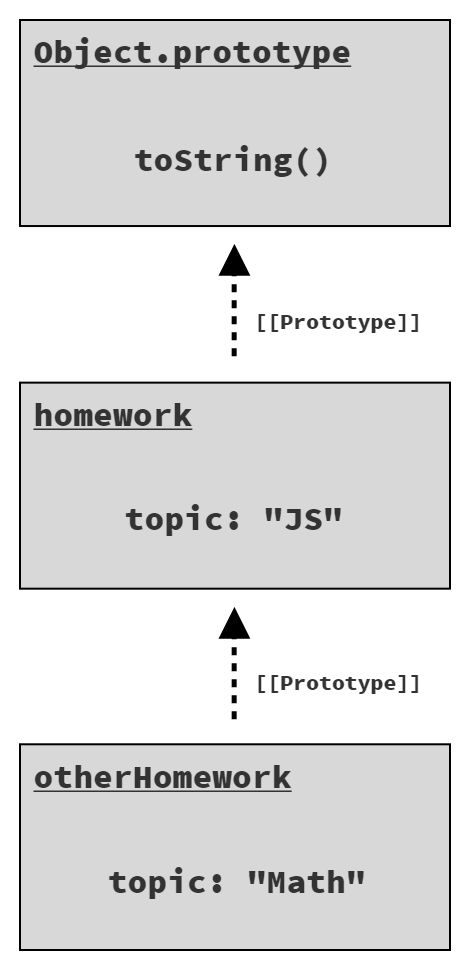

Consider:

homework.topic;

// "JS"

otherHomework.topic;

// "JS"

otherHomework.topic = "Math";

otherHomework.topic;

// "Math"

homework.topic;

// "JS" -- not "Math"The assignment to topic creates a property of that name directly on otherHomework; there’s no effect on the topic property on homework. The next statement then accesses otherHomework.topic, and we see the non-delegated answer from that new property: "Math".

Figure 5 shows the objects/properties after the assignment that creates the otherHomework.topic property:

The topic on otherHomework is “shadowing” the property of the same name on the homework object in the chain.

| NOTE: |

|---|

Another frankly more convoluted but perhaps still more common way of creating an object with a prototype linkage is using the “prototypal class” pattern, from before class (see Chapter 2, “Classes”) was added in ES6. We’ll cover this topic in more detail in Appendix A, “Prototypal ‘Classes’”. |

this Revisited

We covered the this keyword earlier, but its true importance shines when considering how it powers prototype-delegated function calls. Indeed, one of the main reasons this supports dynamic context based on how the function is called is so that method calls on objects which delegate through the prototype chain still maintain the expected this.

Consider:

var homework = {

study() {

console.log(`Please study ${ this.topic }`);

}

};

var jsHomework = Object.create(homework);

jsHomework.topic = "JS";

jsHomework.study();

// Please study JS

var mathHomework = Object.create(homework);

mathHomework.topic = "Math";

mathHomework.study();

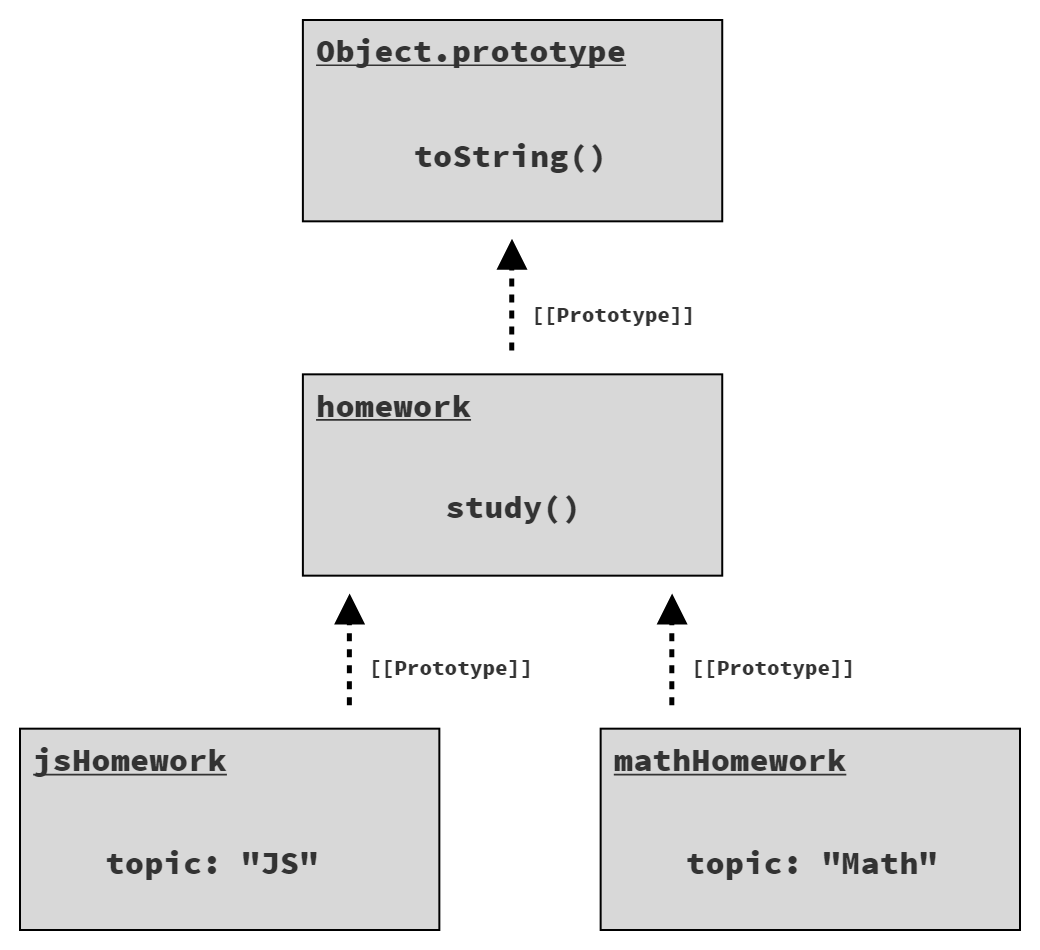

// Please study MathThe two objects jsHomework and mathHomework each prototype link to the single homework object, which has the study() function. jsHomework and mathHomework are each given their own topic property (see Figure 6).

jsHomework.study() delegates to homework.study(), but its this (this.topic) for that execution resolves to jsHomework because of how the function is called, so this.topic is "JS". Similarly for mathHomework.study() delegating to homework.study() but still resolving this to mathHomework, and thus this.topic as "Math".

The preceding code snippet would be far less useful if this was resolved to homework. Yet, in many other languages, it would seem this would be homework because the study() method is indeed defined on homework.

Unlike many other languages, JS’s this being dynamic is a critical component of allowing prototype delegation, and indeed class, to work as expected!

Asking “Why?”

The intended take-away from this chapter is that there’s a lot more to JS under the hood than is obvious from glancing at the surface.

As you are getting started learning and knowing JS more closely, one of the most important skills you can practice and bolster is curiosity, and the art of asking “Why?” when you encounter something in the language.

Even though this chapter has gone quite deep on some of the topics, many details have still been entirely skimmed over. There’s much more to learn here, and the path to that starts with you asking the right questions of your code. Asking the right questions is a critical skill of becoming a better developer.

In the final chapter of this book, we’re going to briefly look at how JS is divided, as covered across the rest of the You Don’t Know JS Yet book series. Also, don’t skip Appendix B of this book, which has some practice code to review some of the main topics covered in this book.